History of Humshaugh

Humshaugh Parish lies to the north-west of the River North Tyne, the western boundary being just inside the Northumberland National Park and the southernmost boundary enclosing a section of the Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage Site. The topography and fertility of the North Tyne valley will have been conducive to prehistoric settlement, although archaeological evidence of this within the Parish is scant. Local Roman history and archaeology is very evident in the form of the remains of Cilurnum or Chesters cavalry fort, to the south of the Military Road at Chollerford. The remains of the Roman bridge, built to carry the defensive wall across the river, is on the Humshaugh Parish boundary. Roman remains continue west through the Parish as far as the turret at Black Carts Farm. The Roman buildings were abandoned during the 5th century and fell into disrepair. There is evidence, throughout the Parish, of the ready-dressed Roman stone having been used as a convenient source of building material.

Evidence of Saxon settlement is rare, although a clue to the early origins of Humshaugh lies in its linear layout, a plan often used in Saxon villages. The original village followed the line of the road from Humshaugh House westwards to the Bellingham road. Any Saxon settlement will have been largely destroyed during the period of savage campaigns waged in the north of England, after the Norman Conquest, known as the ‘Harrying of the North’. In an attempt to suppress rebellion, the Normans laid waste to large areas of Saxon-held territory. As so little of value remained, areas north of the Tees were not included in The Domesday Book. Once things settled down and the Norman barons took control, rebuilding will have taken place and communities re-established.

It is commonly believed that the name ‘Humshaugh’ is Saxon in origin, although it is difficult to know when it came into common use. A rare court document of 1377 refers to ‘Hounsale’. Other documents from the period use the names ‘Hemyshalph’ and ‘Hounshalph’. Possibly all three variations were pronounced in much the same way and were used concurrently. Only the privileged classes were literate, and spelling was not standardised until many centuries later. Original Saxon names were also influenced by the Norman-French language of the overlords.

During the Norman period the area was known as The Liberty of Tynedale and administered largely by local barons, rather than directly by the Crown. During the Anglo-Scottish wars of the 13th century, the Liberty was given to the Scottish kings, who established a seat of government at Wark. The area was essentially a Scottish colony, until the peace treaty that followed the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314; although Norman barons had held much of the power. Existing documents from the late 13th century give information about the county’s great Norman families, but little about the general population. We can only draw upon more general sources to imagine what Humshaugh could have been like. Although administration was local, the Crown had reserved certain rights and one of these was the ability to grant licences to feudal tenants to fortify their manor houses.

Haughton Castle existed as a fortified tower from the 12th century when it was owned by the Widdringtons and was later home to the Swinburnes. By the late 14th century, it was enlarged and designated as a castle. For defensive reasons, a village developed around the castle that was, for centuries, a much larger settlement than Humshaugh. The ruins of the old chapel at Haughton can still be seen. Humshaugh is not marked on Speed’s map of 1610, the nearest marked settlements being Haughton and Walwick. Both are currently small hamlets within our Parish, although, in the early 17th century, would have been more significant than Humshaugh in terms of population.

Humshaugh would have comprised fortified farmhouses and small thatched buildings that made up the farmsteads. This view of Humshaugh is supported by architectural and documentary evidence, and these farmsteads would have been small, consisting of a house, byre and small grass close. The holders would also have had access to scattered strips of land, varying in quality, and a share of meadow and common pasture on the fell. We can still see the patterns of the strip system of farming in the old undisturbed pastures in the Parish.

An old set of deeds from the 1270s refer to a John Swinburne owning the manor of Humshaugh. The Manor House, now Humshaugh House, has architectural evidence suggesting 13th century origins, whilst 16th and 17th century features support the idea that the house was a bastle, or fortified farmhouse. Bastles were often grouped together within an area to give greater protection to the residents of the vicinity, and this was the case in Humshaugh. Five buildings in the present village have strong architectural features, suggesting that they were bastles. Besides Humshaugh House, are Dale House, Dale Cottage, Teasdale House and Linden House. Such fortified buildings were necessary during Tudor times, when reiving was rife in the unsettled border lands. This feuding involved both cross border skirmishes and inter-family feuding within the county. Evidence of the reiving clans exists in local surnames, such as Charlton, Milburn, Dodd, Robson and Elliott.

Bastles were usually two-storey rectangular buildings with walls up to a metre thick and small windows for defensive purposes. They afforded protection to families on the upper floor and to their farm animals below. In more settled times, after the Civil War, some bastles were altered and developed into comfortable domestic homes and we can see evidence of this in Humshaugh. Dale House has a date stone showing that the building was ‘modernised’ in 1664 and a stone inscribed 1690 tells a similar story at Teasdale House. One presumes that developments at both Humshaugh House and Linden House were happening around the same time.

Although of insufficient significance to be marked on John Speed’s map of 1610, the village is shown on Armstrong’s map of 1769. It is marked as a small collection of buildings in a linear plan. Humshaugh Manor is shown at the east end of the village and, at the west end, the large house shown is most likely the current Linden House. The other buildings shown will have been the small farms that made up the village. Humshaugh remained a small agricultural settlement until the beginning of the 19th century, when the owner of Haughton Castle, William Smith, started renovations to create a comfortable family residence. At the same time, he laid out parkland in front of the castle, involving the demolition of Haughton village. The displaced people were removed to Humshaugh, where accommodation was provided for them. Many of these people worked at the Haughton Paper Mill and, even by 1851, the census shows that a large number of Humshaugh residents were still employed at the Haughton Paper Mill.

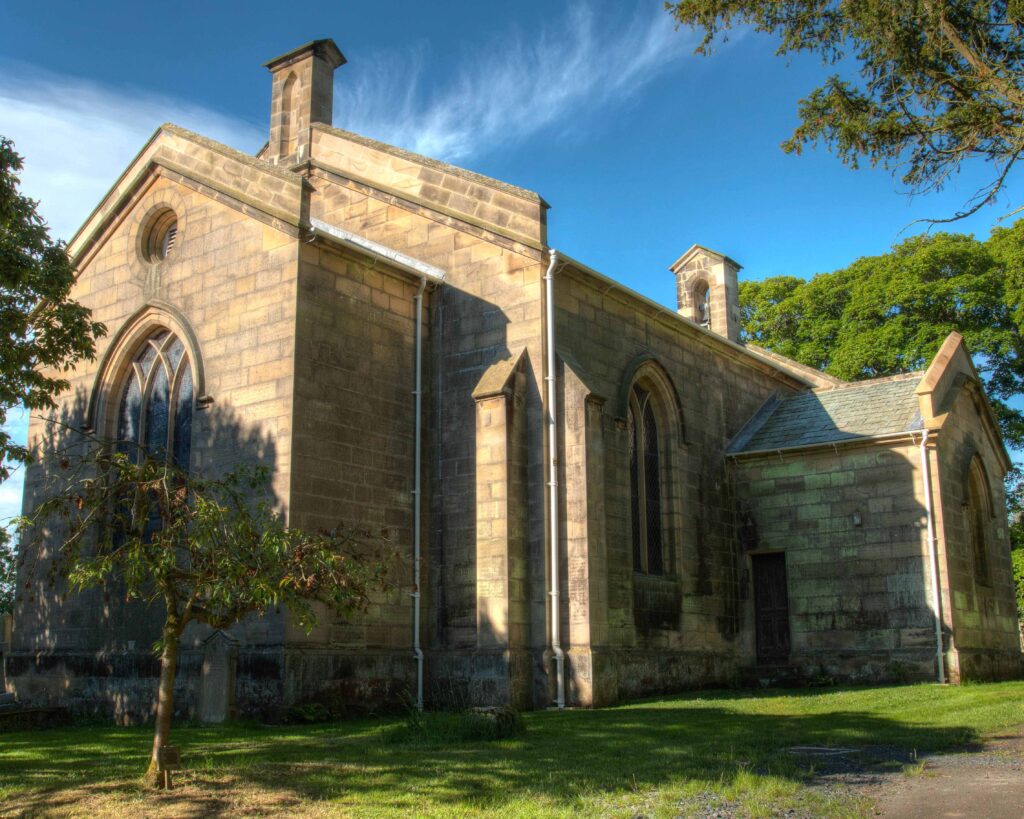

As part of the ecclesiastical reorganisation of Simonburn Parish by the landowners, Greenwich Hospitals, St Peter’s church was built in Humshaugh and consecrated as a chapel of ease in 1818, increasing its significance as a village. The growth of Humshaugh is reflected in Fryer’s Map of 1820 and the Greenwood Map of 1828. There is supporting documentary evidence in the writing of Newcastle publisher and historian, Eneas Mackenzie. In his ‘View of the County of Northumberland’, published in 1825, he described Humshaugh as having four or five farms, a public house and a few cottages for labourers.

The ‘public house’ will have been The Crown Inn, which, by then, may have been in the village for over a century. The inn is claimed to have been built in 1703, although sources have not been verified. It will have been a coaching inn for travellers in the North Tyne valley, but evidence exists that farming also took place there. This is also true of The George Inn at Chollerford, which dates from the mid-18th century and was developed on the site of the old ferry boat house. It is concurrent with the building of the Military Road and will have provided coaching facilities for travellers on the new east to west route. It is also known that there was a coaching inn at Walwick.

The Military Road is always associated with Field Marshall George Wade, who had difficulties in moving his troops from Newcastle to Carlisle in November 1745, during the Jacobite rebellions. He made complaints about the state of the road from east to west, which was then designated as a ‘summer road’, but he died in 1748. It is unlikely that he had any involvement in the planning of the new road. A local man, Lancelot Allgood of Nunwick, was at this time an MP and Sheriff of Northumberland and he was actively involved in the building of the new road, which was completed in 1758. Chollerford Bridge, carrying the road over the North Tyne had been damaged several times by floods and was finally demolished in the great flood of 1771. The new bridge, built by Robert Mylne in 1785, has stood the test of time and is still coping with modern-day traffic.

Improved road communications will have benefited the prosperity of Humshaugh, as would the coming of the Border Counties Railway a century later. Chollerford Station was opened in 1858 and was later renamed as Humshaugh Station, to avoid confusion with Chollerton further along the line. Better links with Hexham and beyond helped businesses in Humshaugh to thrive. This once agricultural settlement was now an almost self-sufficient hub of commercial activity. Directories from the latter half of the 19th century show increasing numbers of tradespeople, i.e. blacksmiths, carpenters, shoemakers and tailors, as well as drapers, grocers, bakers and butchers. The village has had its own school, since 1833, and a Wesleyan chapel was built in 1862. Humshaugh’s GP served the large rural area that made up District 4 of the Hexham Union. Other medical professionals, such as pharmacists and trainee doctors supplemented the medical services in the village.

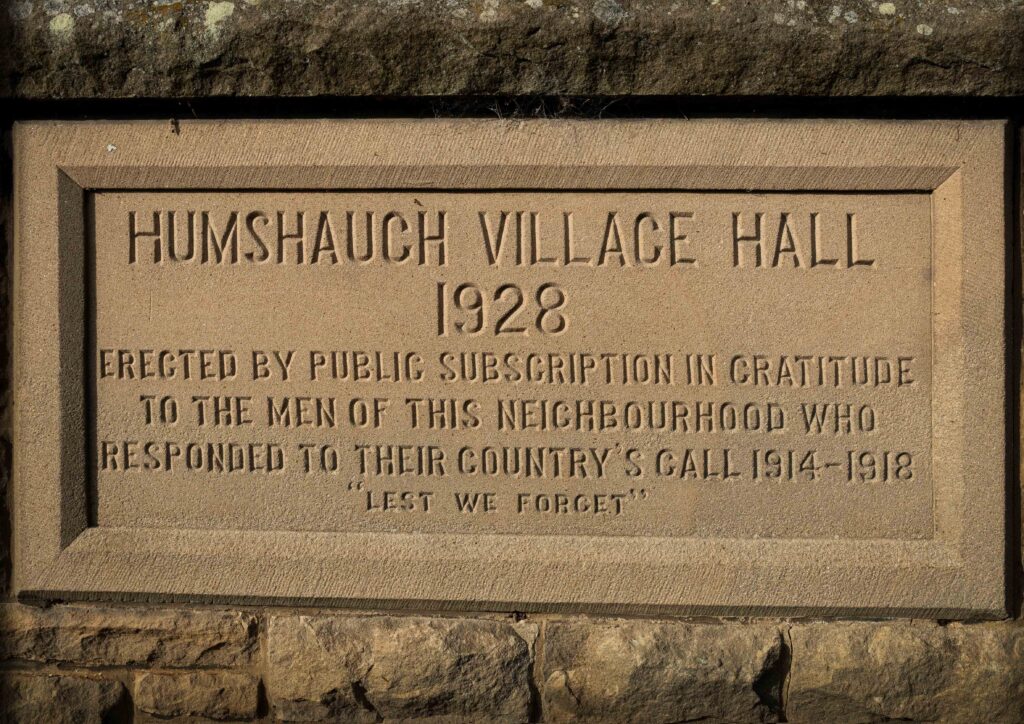

During the course of the 19th century the range of employment opportunities had widened and included more jobs in the local quarries and on the roads and railways. The 1911 census shows that people were taking up new employment opportunities in Hexham and that more young women were choosing to do jobs other than domestic service. The recruitment records of the young men who volunteered for military service in 1914, show that a fair proportion of them were still employed on the big estates in the Parish. Of the men who served their country in WW1, the village remembers fifteen on the War Memorial unveiled in 1920, and on a plaque in St Peter’s Church. It was also the wish of the people of Humshaugh to have a village hall, as a memorial to those lost in the Great War. After much fund-raising and generous public subscriptions, the Hall was built and finally opened in 1928.

Until the middle of the 20th century, Humshaugh had retained its predominantly linear form, few buildings having been constructed between The Crown Inn and Chollerford. On the west side of the road were St. Peter’s Church, the vicarage, the Village Hall, Humshaugh School and Hopewell House, formerly the residence of the head teachers. The east side of the road to Chollerford was largely agricultural land until the late Victorian mansion, Wayne Riggs, was built. Between there and the Orchard, the council built ten houses, known as Wayne Riggs Terrace. Planned and started in the late 1930s, the terrace wasn’t completed until the late 1940s, because of WW2. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was little development in the village apart from several individual houses to the east of Wayne Riggs and on other plots of undeveloped land throughout the village.

During this period the school was enlarged, two-storey extensions being added to each end of the building, creating three new classrooms. The original village school catered for children of all ages, up to the school-leaving age of 14. Northumberland Archives hold a 1930s plan for a proposed secondary school to be located near the primary school, on the land that we know as Valley Court. The outbreak of war prevented this from going ahead and, by the time the war ended, the 1944 Education Act had been passed. The major change outlined in this Act was the raising of the school-leaving age to 15, although it was not implemented until after the end of the war. The new school planned for Humshaugh lacked the facilities required for practical subjects and did not comply with the 1944 Act.

Overall reorganisation of secondary education in Northumberland made the need for small secondary schools redundant, leaving the land between the school and St. Peter’s churchyard undeveloped until the early 1970s, when 14 large bungalows were built in spacious plots of land to create Valley Court. This was the first estate of executive housing to be built in the village, providing up-to-date, stylish homes for an affluent group of people. The development is outside of the Conservation Area and built very much in the style of the period. Although conflicting with the historical ambience of the village, the houses are set high from the road and are largely hidden from view.

In 1982, the new doctor’s surgery and health centre was built, bringing enhanced medical facilities to the village. Around the same time, the council built senior residents’ bungalows, providing convenient, modern homes for older citizens in the village. Four bungalows were built on the land between the church and Widdrington Terrace and two more were created from the building on the main road that was once the old reading rooms, completing Orchard View. Eight more local authority bungalows were built beyond the new surgery on East Lea.

The mid-1980s saw the building of executive bungalows at Hadrian Court, which was extended in the 1990s making 18 bungalows in total. Close to Chollerford roundabout, this estate is nevertheless accepted as being part of Humshaugh. Again, the Hadrian Court is very much of the period, yet, being bungalows, is of low visual impact.

In 1992, a housing association built 18 new houses, known as East Lea, behind Wayne Riggs Terrace. Around the same time work was started on the redevelopment of the site at East Farm, when old agricultural buildings were cleared to make way for 6 new houses. This small development of executive housing, within the Conservation Area, was completed in 1994. Although some traditional features were incorporated into the buildings, the cul-de-sac arrangement of the houses has subsequently been criticised for not being in keeping with the historical layout of older buildings in the village.

An old Ministry of Defence building, later known as ‘the factory’, lay between the playing field and Hadrian Court. Built as a storage depot during WW2, the building was used after the war, by a firm called Bowmaker, in turn taken over by a Leeds firm called Evans. They were a mechanical engineering business, who bought up and reconditioned surplus military machinery and vehicles. These were sold to the governments of newly-independent countries. The building was later used as a repair shop for agricultural vehicles and machinery. When ‘the factory’ closed, it stood empty, becoming an increasing eyesore, until the mid-1990s, when Anvil Homes bought the derelict site. The old factory was demolished, and Beechcroft built. Old, reclaimed stone was used for the houses and boundary walls, which adds to the charm of this development. The 24 houses vary in size and design and the layout of this small estate enables it to sit comfortably within its village situation. Beechcroft, named after the fine preserved beech trees that have been incorporated into the design, is arguably the most aesthetically pleasing of all the new housing built in Humshaugh in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

There were no significant changes within the village until 2015, when a small estate of affordable housing was built behind The George Hotel. Although considered part of the village, the location of these 14 houses can more accurately be described as Chollerford. Built on a field that used to belong to the hotel, the development was named Simmonds Court, as a tribute to a previous owner of The George. James Simmonds was one of our local unsung heroes, who was heavily involved in fund-raising events during WW1. Simmonds Court was the first housing of its type to be built in the village since East Lea in the early 1990s. It is a very pleasing development and, in 2016, won a national Housing Excellence Award, for the Best Small Affordable Housing Scheme.

In 2016, Duchy Homes was given planning permission to build 21 houses on the field opposite Humshaugh School. Although houses of 2, 3, 4 and 5 bedrooms were built, it is the larger houses that dominate the scheme. Chesters Meadow is a compact development and, although they are individually attractive, the houses bordering the main road are large and have completely altered the once open view from the school. As time passes and gardens mature, this change, like many others in the past, will become assimilated into the village environment. The whole site was not landscaped as the developers promised and, in 2019, Duchy Homes applied for permission to build a further 20 houses on the remaining land. This permission was refused.

At the same time the developers Cussins started work on land behind the East Lea houses that previously belonged to Haughton Castle. It is an attractive, low-density development, totally hidden from the main road through the village. As completed, Haughton Place and St Peter’s Way comprises twenty three 3, 4 and 5-bedroomed houses. The larger houses dominate the scheme, although they are not crowded, being set in larger plots.

In 1911, the population of Humshaugh was 519 and, by 2021, it had only risen to 713. Despite many newer houses in the village being larger, they generally accommodate fewer people than would have been the case in 1911. In 2023, our village is still a thriving community, although made up of more commuters and retired people. We are benefiting greatly from a diverse set of new residents, who are supporting the many activities that take place in Humshaugh, enabling our community institutions to thrive.

Many thanks to Jen for the research & words and Chris for the photos.